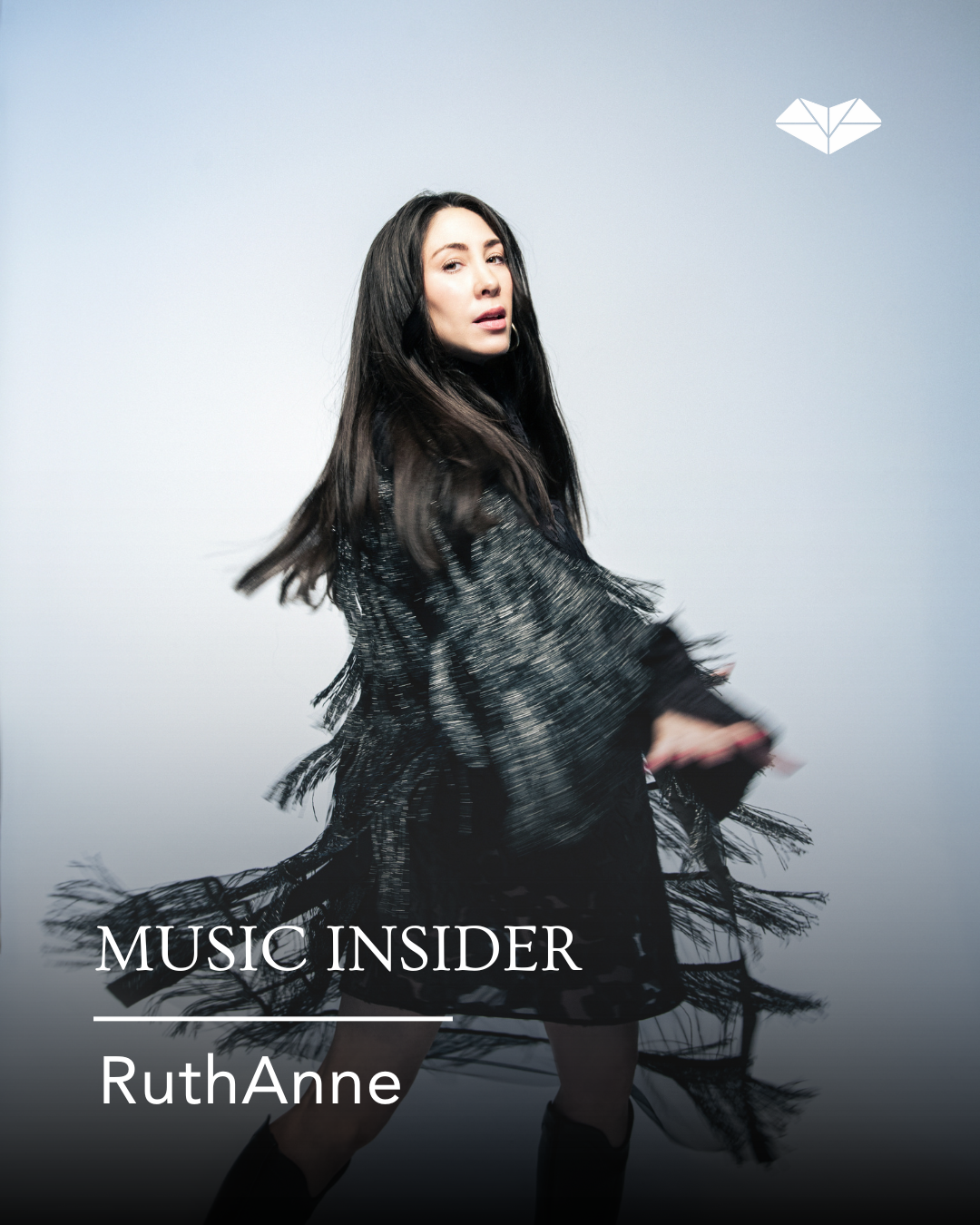

Photo Credit: Harlan Finch

For more than twenty years, Jenn Barker has built a reputation as one of the most versatile and quietly influential operators in the arts and entertainment landscape. Her work spans independent labels, international touring, festival leadership, higher education, and the development of new management models that prioritise transparency and artist ownership.

Barker helped steward releases at Mint Records during a defining era, working on projects including the New Pornographers’ Twin Cinema and Neko Case’s Fox Confessor, before moving into tour management and later founding Your Operator, where she supported artists such as Destroyer, A.C. Newman, The Pack A.D., and others across North America.

In education, Barker reshaped the curriculum at Nimbus School of Recording, ultimately becoming Head of the Music Business Department and co-founding Business Class Records, a student-run label that went on to achieve national radio chart success and inspire similar initiatives at other institutions.

Since launching Fairground Management in 2019, she has worked with internationally recognised artists including Destroyer, Imaad Wasif and Spencer Krug, while mentoring emerging managers and building systems designed to help artists operate with clarity, control and long-term stability.

Fairground’s expansion now includes a distribution partnership with FUGA, a mentorship-driven label (play dead), and a new publicity wing, Playground PR. Across all of it, Barker’s focus remains consistent: designing artist-centred infrastructures that cut through outdated hierarchies and give creators the tools to run sustainable careers on their own terms.

What inspired you to start Fairground, and how did you shape it into a space that bridges management, label services, and mentorship?

What I love most is helping people find their spark or vision and then build the business systems to support it. Whether an artist is just starting out or already established, there will always be times when they need to reinvent themselves and their business models. For some artists, that means hands-on management; for others, it’s mentorship or co-piloting their label.

The goal is to help artists become cultural entrepreneurs who understand their own ecosystem. I wanted to build something transparent - a management model that empowers artists with the knowledge to make their own decisions and expand their revenue streams.

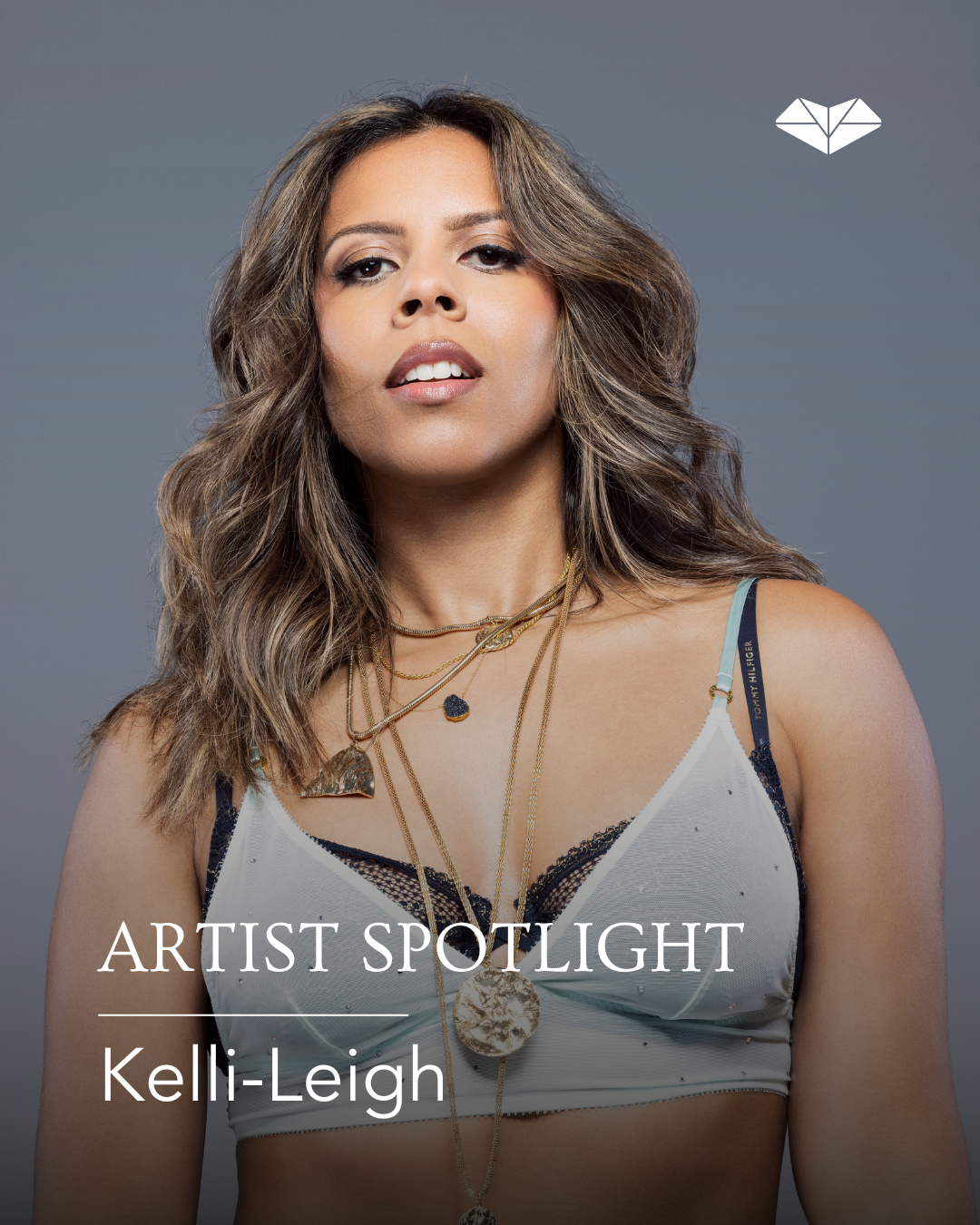

Photo Credit: Harlan Finch

I started off working in artist management and product management at record labels, then eventually moved into financial management and post-secondary education. I created a hybrid of all those experiences: part manager, part label, part mentor, and part business manager. It felt like the most natural way to combine everything I’d learned into something that could support artists in real time.

Fairground grew out of seeing the same issues - labels and artists not keeping their books straight, poor creative rights management and profits evaporating after everyone else took their cut leaving artists struggling. I wanted to adapt to the current reality of the music industry by moving away from the old hierarchies that kept artists in the dark and build a model that supports how they work.

A lot of artists are self-directed but they need better systems to support the business and financial sides of their work. The framework stays consistent and streamlined, but how we move within it shifts with each artist and release cycle. To me, that’s what an adaptive model looks like - flexible and collaborative without the top-down dynamic that kept too many artists shut out of their own business.

How can artists start thinking more sustainably about their careers, especially when resources are limited?

Sustainability starts with understanding how your operation functions and what skills or resources you already have that you can build from. I like to encourage artists to take an inventory of their strengths. Many of the skills they already use creatively - design, video editing, production, writing - can translate into services or income streams that support the bigger picture.

Artists who embrace entrepreneurial thinking gain agency, create their own job markets and build careers that align with their timelines and album cycles

The traditional industry model doesn’t offer much return early on, which is why smaller music communities matter. Sharing skills, collaborating locally, and reinvesting within those circles helps to pave the way. It’s about helping artists understand their value, setting up systems that support their goals and building an ecosystem where their creativity, income, and community can grow together. Those networks are where sustainability starts to take root.

What do you think makes a strong artist–manager relationship work in practice?

There’s no single formula for what makes an artist–manager relationship work. It’s both professional and deeply personal, so it takes time, trust, and discernment to find the right fit. The best partnerships are built on mutual respect and a shared understanding of what each person brings to the table.

Good communication and boundaries are essential. I’ve learned that a manager’s job isn’t to carry all the emotional labor. Empathy and support are important, but it becomes unsustainable if that’s all the artist relies on you for. The relationship works best when the artist also values your professional insight.

Education can be part of building trust. When artists understand how their business operates and what decisions need to be made - they’re better equipped. That mutual awareness is what allows both sides to work together with clarity and purpose.

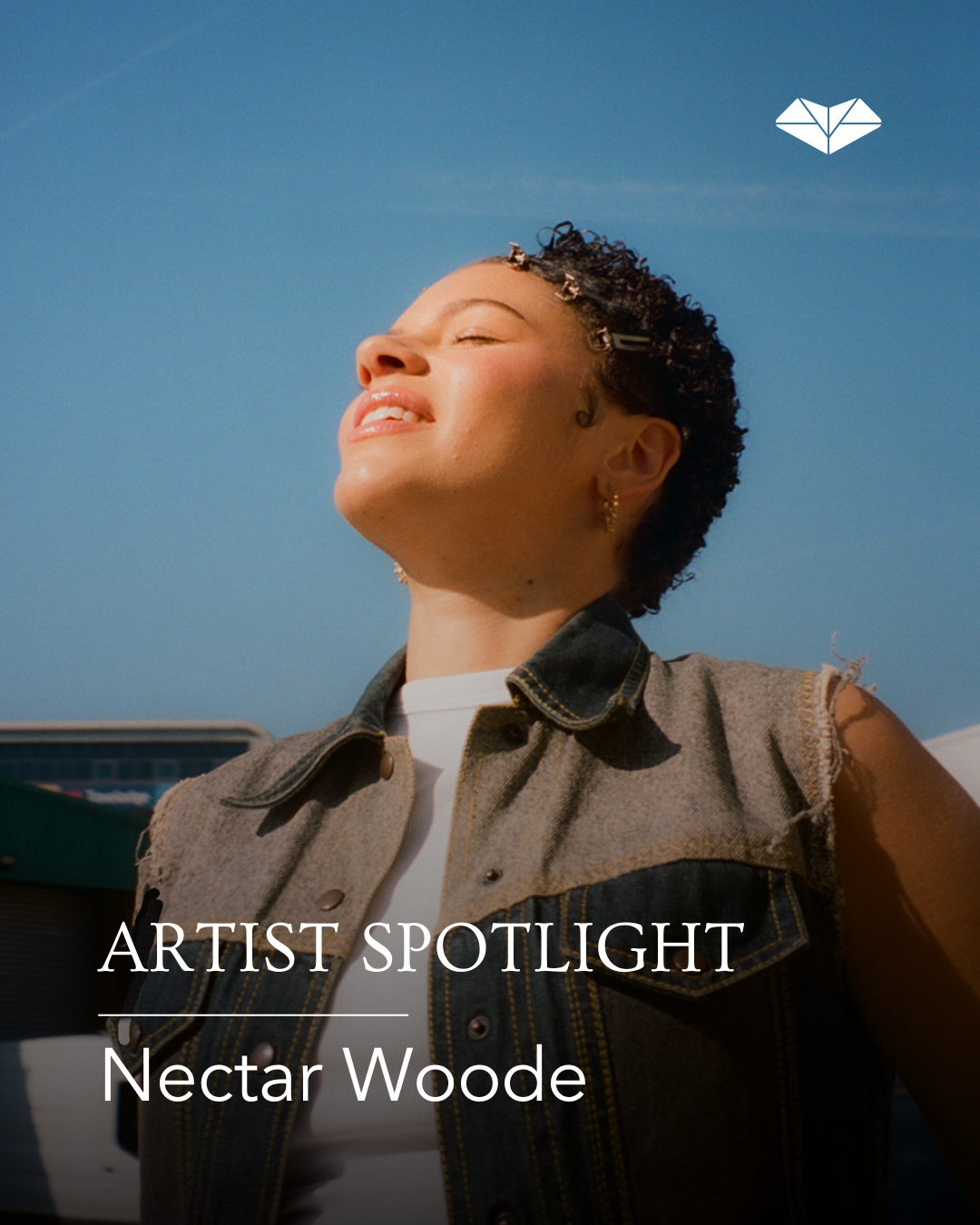

Photo Credit: Harlan Finch

You’ve spoken about creating smaller, more effective teams. What roles or skills do you think are most essential for artists to prioritize when building theirs?

Start by choosing people who can grow with you. That might mean bringing in emerging creatives who can wear multiple hats and share your vision - enthusiasm matters as much as experience.

Every artist’s needs are different, but a few core skills make the biggest difference early on: someone who can keep timelines realistic; someone who understands budgets and basic financial oversight; someone who can translate the art into marketing and communication; and someone who understands metadata, creative rights, and merch/touring logistics.

These don’t all need to be separate roles - someone can cover two or three areas. What matters most is knowing where you need help and what you can realistically handle yourself.

Smaller, informed teams tend to move faster and keep more revenue in-house. It’s not about building the biggest team, it’s about building the right one. The strongest teams share alignment and a willingness to stay curious and adjust as the project grows. The fewer outside companies involved, the less you lose to hand-offs and oversight gaps - giving you the chance to build your own in-house operating system instead of relying on everyone else’s.

For artists trying to navigate the balance between independence and growth, what’s your advice on when to bring in professional support?

I think the best time to bring in professional support is when you already have a bit of momentum - when you’ve figured out what you want to build and what kind of help will move it forward. A good manager or label should complement your direction, not define it.

A lot of artists jump straight to wanting a manager, but sometimes what they really need first is mentorship or industry guidance. When you know how your business functions and which partnerships truly serve it, delegation stops being a gamble.

Growth doesn’t always mean outsourcing everything. Sometimes it’s about building capacity from within and then using that knowledge as leverage to negotiate better deals or partnerships later on. The goal is empowerment, not dependency. The right kind of professional support should open more doors and insights for you, not absorb your autonomy.

You’ve helped many artists run their own record labels. What are the biggest lessons or pitfalls to avoid for anyone trying to do that?

Keep your books and metadata clean from day one - that’s the foundation everything else rests on. A lot of labels starting out skip this step and end up losing track of royalties and rights. Take the time to research your genre tags too - they directly affect where your music gets placed and discovered, so make sure they’re accurate and consistent across all platforms. Always back up your metadata: keep a clear record of ISRCs, UPCs, splits, and credits in one place. You’ll thank yourself later.

Before signing any distribution deal, really take the time to understand what royalties are covered and how it affects your rights as a master owner. A lot of artists assume distribution is just a simple upload process, but every agreement has its own structure, and those small details can make a big difference later on. Increasingly distro deals also include clauses that allow your music to be used for AI training or derivative works, so it’s critical to read the fine print and understand exactly what you’re agreeing to.

Another common pitfall is skipping the numbers when it comes to manufacturing. Use your data - sales history or fan engagement - to make informed projections before you invest. Guessing too high on physical products can be an expensive lesson.

Running a label as an artist means wearing two hats. The creative side is about vision and storytelling; the label side is about systems, data, and pacing. Both can coexist, but they require different modes of thinking. The artists who do it best are the ones who can shift between those modes - knowing when to zoom in creatively and when to zoom out strategically.

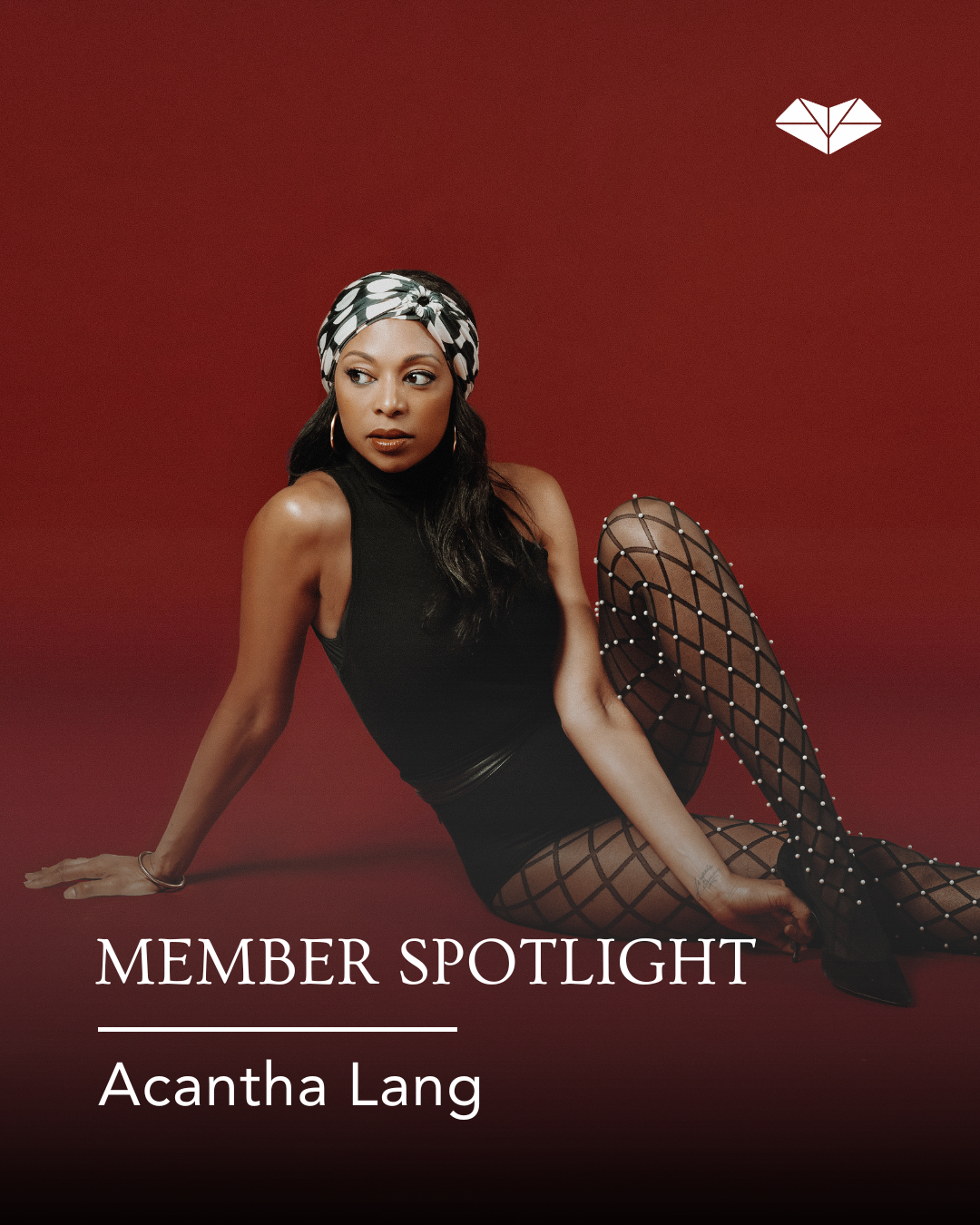

Photo Credit: Harlan Finch

How can emerging managers or artists learn to read and use their own data more strategically without losing sight of the creative process?

I think it starts with redefining what “strategic” actually means. It’s a mirror, not a map. It isn’t about gathering more numbers - it’s about understanding the story they reveal about your audience, your momentum, and where your work is connecting. Data only becomes useful when it’s legible, and that looks different for everyone. Some people love spreadsheets; others need things visual or narrative. The format matters far less than finding one you can genuinely learn from.

The important part is deciding what you want to measure before you begin a project. Don’t let the industry’s default metrics dictate your goals. Define success in a way that reflects your goals and values - maybe it’s your return on investment, whether it reached the audience you intended or whether a new idea created engagement you can repeat.

When you choose metrics that answer your questions, you get data you can refine and build from. It’s not about turning anyone into an analyst; it’s about connecting the dots between the art, the audience and the income. Data should reflect the creative reality that already exists - it shows you what is resonating, not where to go next. Numbers can reveal patterns, but they can’t replace intuition.

The real challenge is using data as a tool for awareness rather than validation. We’ve spent too much time measuring our worth by metrics that we’ve drifted away from the community connection that gives those numbers meaning. As the industry continues to prioritise metrics over artistry, returning to real artist development becomes one of the strongest ways to push back - to focus on longevity instead of virality.

With so much pressure to stay visible online, what are some ways you personally unwind or reset on a difficult day?

I’ve been lucky to tend the same garden for sixteen years and it’s become my anchor. Growing food and plant medicine has taught me to think in seasons, not sprints - to visualize how things come together over longer spans of time. It reminds me that growth isn’t linear; it’s cycles of tending, pruning, and rest.

Every year I divide my plants and share them with neighbours. It’s a small ritual but it builds community, a quiet reminder that generosity often begins close to home and that there’s power in sharing resources to support someone else’s vision. In many ways, it mirrors how I approach my work in music: plant the seeds, nurture them and know when to create space for things to grow.